European Food Safety Authority: A playing field for the biotech industry

Excerpts from Christoph Then and Andreas Bauer-Panskus's 2010 report for Germany-based NGO Testbiotech, "European Food Safety Authority: A playing field for the biotech industry", are reproduced or paraphrased below and referenced elsewhere across the GMWatch Portal. The original report is available online at Testbiotech or can be downloaded directly.

In summary, the report investigates conflicts of interest within the GMO Panel membership to demonstrate how the Panel's relationship with the biotech industry - and in particular via the influence of a task force of the International Life Sciences Institute (ILSI) - resulted in comparative assessment being taken as the starting point in the EFSA guidelines on risk assessment of genetically engineered plants. Comparative assessment, an approach to risk assessment which assumes equivalence between conventional breeding and genetic engineering, has serious implications for the scientific rigour of research into the risks of genetically engineered plants. The authors of the report highlight the potential for further problems given the fact that the databank for such research was set up by the ILSI - an arrangement which 'does not appear to provide adequate protection from targeted manipulation by industry'. Additionally, the authors found that a document published by the EFSA to explain why feeding trials are not required to test for potential health impacts of genetically engineered plants 'was partially plagiarized from an ILSI paper'. The authors suggest that it is 'likely this is only the tip of the iceberg'.[1]

The Testbiotech report explains that risk assessment required by EU regulations is premised on the precautionary principle[2] and should therefore be designed to ensure safety for consumers and environment. The EFSA is tasked with 'the practical application of these regulations in the context of market applications'. Led by Suzy Renckens, the GMO Unit was established to oversee the GMO Panel, an expert panel originally chaired by Harry Kuiper of the RIKILT research institute at Wageningen UR. Risk assessment guidelines were published by the Panel in 2004, followed by further documents addressing other areas of risk assessment including environmental risk assessment, animal feeding trials, allergenicity risk and monitoring.[3] Testbiotech cite an EU Commission report from 2006[4], observing that 'There has been a lot of criticism from various stakeholders that the work of EFSA is inadequate to fulfil EU requirements.' The authors explain how reports prepared by the GMO Panel have additionally 'failed to gain necessary majorities in the EU Council voting'.[3]

The Testbiotech report identifies the International Life Sciences Institute (ILSI) and the former GMO Panel chair, Harry Kuiper, as the 'most relevant drivers' in terms of industry influence on EFSA guidelines, as will be outlined in more detail below.[3]

Describing the 'alarming degree' to which the work of the EFSA GMO Panel has been influenced by the vested interests of industry, Testbiotech makes the following recommendations:

- EFSA should be reorganised at management and GMO Panel levels

- Experts working for ILSI should step down from their positions at EFSA.

- A commission including representatives from the general public should be set up to investigate current EFSA standards and the extent to which EFSA has been undermined by industry. Under these circumstances, EFSA guidelines should not be adopted as EU regulations as currently planned by the EU Commission.[5]

- EFSA should establish an additional control body, integrating stakeholders from civil society such as environmental and consumer organisations.[6]

How the ILSI impacts the EFSA risk assessment of genetically engineered plants

The authors of the Testbiotech report argue that 'The collaboration between ILSI and the GMO Panel has had a marked effect on EFSA,' referencing the claims of the ILSI itself as to the impact of their task force on EFSA guidelines for risk assessment.[1]

As the Testbiotech report notes, the US-based ILSI maintains it is free from corporate influences[3]:

- The International Life Sciences Institute (ILSI) is a non-profit worldwide foundation established in 1978 to advance the understanding of scientific issues relating to nutrition, food safety, toxicology, risk assessment, and the environment. ILSI also works to provide the science base for global harmonization in these areas.

- By bringing together scientists from academia, government, industry, and the public sector, ILSI seeks a balanced approach to solving problems of common concern for the well-being of the general public.[7]

Despite such proclamations, the WHO publicly objected to what was perceived as close cooperation between the ILSI and the tobacco industry.[8] The ILSI was at the centre of further controversy over the involvement of Diána Bánáti, a member of the EFSA management board. Bánáti subsequently stood down from the EFSA.[9] It was reported in German media that the ILSI influenced risk assessment for potentially hazardous chemical compounds such as Bisphenol A.[10]

The ILSI Task Force

The Testbiotech report authors argue 'there is no doubt that ILSI has a very close connection to industry', particularly in relation to the agri-biotechnology industry.[11] The Task Force on biotechnology established by ILSI is comprised entirely of industry members, including BASF, Bayer CropScience, Dow AgroSciences, Monsanto, Pioneer Hi-Bred/Dupont and Syngenta. As ILSI suggests, 'Although disbanded, the Task Force continues to have impact.'[12]

ILSI's involvement in agri-biotechnology dates from at least 1996, around the time at which Monsanto began the commercial production of genetically engineered soy. 'At that time', the report authors note, 'agri-biotechnology faced the difficulty of opening up the European market for its new controversial products.'[11]. In 1997, ILSI Europe established the Novel Foods Task Force to deal with the safety assessment of novel foods[13]

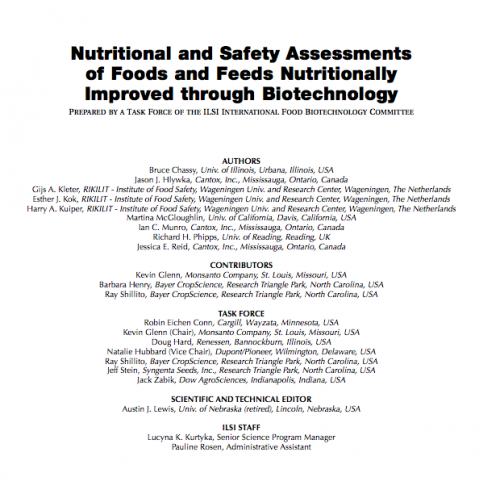

The RIKILT team at the University of Wageningen in the Netherlands and their experts Harry Kuiper, Gijs Kleter and Ester Kok were among those working with ILSI.[11] Harry Kuiper had already worked with ILSI in 1998, chairing a workshop on 'Detection methods for novel foods derived from genetically modified organisms' organised by the ILSI Europe Novel Food Task Force in collaboration with the ILSI International Food Biotechnology Committee.[14] The Testbiotech report asserts that Harry Kuiper, Gijs Kleter and Ester Kok worked together for the ILSI from around 2001.[11] They are also among the authors of a 2004 report for the ILSI Task Force, 'Nutritional and safety assessments of foods and feeds nutritionally improved through biotechnology'.[15] Alongside his work at ILSI, Harry Kuiper was also chair of ENTRANSFOOD, an EU project supported by the European Commission and industry partners to research safety assessment of genetically modified food crops. As such, 'Harry Kuiper was one of the most influential experts in Europe at a time when he was under contract to ILSI.'[16]

While working for the ILSI Task Force, Kuiper, Kleter and Kok published several papers on the risk assessment of genetically engineered plants which included references to ILSI concepts. Of particular interest is the concept of comparative assessment - the starting point for the risk assessment of genetically engineered plants in the guidelines produced by EFSA's GMO Panel.[16]. See, for example:

- Kuiper H.A., Kleter G.A., Noteborn H.P.J.M., Kok E.J, 2001, Assessment of the food safety issues related to genetically modified foods. Plant J 27:503–28.

- Kok, E.J., Kuiper, H.A., 2003, Comparative safety assessment for biotech crops. Trends in Biotechnology 21: 439–444.

- Kuiper H.,A. & Kleter G.,A., 2003, The scientific basis for risk assessment and regulation of genetically modified foods, Trends in Food Science & Technology 14 (2003) 277–293

Contributors to the Task Force report, 2004

From a 2004 report by the Task Force of the ILSI International Food Biotechnology Committee.[15]

Authors

- Bruce Chassy, Univ. of Illinois, Urbana, Illinois, USA

- Jason Hlywka, Cantox, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada

- Gijs Kleter, RIKILT - Institute of Food Safety, Wageningen Univ. and Research Center, Wageningen, The Netherlands

- Esther Kok, RIKILT - Institute of Food Safety, Wageningen Univ. and Research Center, Wageningen, The Netherlands

- Harry Kuiper, RIKILT - Institute of Food Safety, Wageningen Univ. and Research Center, Wageningen, The Netherlands

- Martina McGloughlin, Univ. of California, Davis, California, USA

- Ian Munro, Cantox, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada

- Richard Phipps, Univ. of Reading, Reading, UK

- Jessica Reid, Cantox, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada

Contributors

- Kevin Glenn, Monsanto Company, St. Louis, Missouri, USA

- Barbara Henry, Bayer CropScience, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, USA

- Ray Shillito, Bayer CropScience, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, USA

Task Force

- Robin Eichen Conn, Cargill, Wayzata, Minnesota, USA

- Kevin Glenn (Chair), Monsanto Company, St. Louis, Missouri, USA

- Doug Hard, Renessen, Bannockburn, Illinois, USA

- Natalie Hubbard (Vice Chair), Dupont/Pioneer, Wilmington, Delaware, USA

- Ray Shillito, Bayer CropScience, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, USA

- Jeff Stein, Syngenta Seeds, Inc., Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, USA

- Jack Zabik, Dow AgroSciences, Indianapolis, Indiana, USA

Scientific and technical editor

- Austin Lewis, Univ. of Nebraska (retired), Lincoln, Nebraska, USA

ILSI staff

- Lucyna Kurtyka, Senior Science Program Manager

- Pauline Rosen, Administrative Assistant

Contributors to the Task Force report, 2008

From a 2008 report by the Task Force of the ILSI International Food Biotechnology Committee:[17]

Authors

- Bruce Chassy, Univ. of Illinois, Urbana, Ill., U.S.A. Marceline Egnin, Tuskegee Univ., Tuskegee, Ala., U.S.A.

- Yong Gao, Monsanto Co., St. Louis, Mo., U.S.A.

- Kevin Glenn, Monsanto Co., St. Louis, Mo., U.S.A.

- Gijs Kleter, Wageningen Univ., The Netherlands

- Penelope Nestel, Inst. of Human Nutrition, Univ. of Southampton, U.K.

- Martina Newell-McGloughlin, Univ. of California, Davis, Calif., U.S.A.

- Richard Phipps, Univ. of Reading, Reading, U.K.

- Ray Shillito, Bayer CropScience, Research Triangle Park, N.C., U.S.A.

Task Force

- Bryan Delaney, Pioneer Hi-Bred/A DuPont Co., Johnston, Iowa, U.S.A.

- Kevin Glenn, Chair, Monsanto Co., St. Louis, Mo., U.S.A.

- Daland Juberg, Dow AgroSciences, Indianapolis, Ind., U.S.A.

- Catherine Kramer, Syngenta Biotechnology, Research Triangle Park, N.C., U.S.A.

- David Russell, Renessen LLC, Bannockburn, Ill., U.S.A.

- Ray Shillito, Bayer CropScience, Research Triangle Park, N.C., U.S.A.

Scientific and technical editor

- Austin Lewis, Univ. of Nebraska (retired), Lincoln, Nebr., U.S.A.

- Christina West, Nashville, Tenn., U.S.A.

ILSI staff

- Lucyna K. Kurtyka, Senior Scientific Program Manager (until July 14, 2006)

- Marci Levine, Staff Scientist (after July 25, 2006)

- Melinda Thomas, Administrative Assistant (until August 14, 2006)

- Janice C. Johnson, Administrative Assistant, (after September 25, 2006)

ILSI, EFSA and the concept of Comparative Assessment

As the report explains, comparative assessment is a concept based on a comparison between genetically engineered and conventionally bred plants, in which equivalency is assumed if no significant differences are identified in across the most important components of the plants.[16] According to the EFSA,

- The underlying assumption of this comparative assessment approach for GM plants is that traditionally cultivated crops have gained a history of safe use for the normal consumer or animal and the environment. These crops can serve as a baseline for the environmental and food/feed safety assessment of GMOs.[18]

The authors of Testbiotech report observe, however, that while comparative assessment helps simplify risk assessment, if genetically engineered plants were considered to be substantially different from conventional plants because of the methods used in their production - 'much more plausible from a scientific point of view' - a broader concept and more comprehensive risk assessment would be required.[16] For more discussion on this, see Then & Potthoff, 2009.

The EFSA notes:

- Where no appropriate comparator can be identified, a comparative safety assessment cannot be made and a comprehensive safety and nutritional assessment of the GM crop derived food/feed per se should be carried out.[19]

Comparative assessment builds on the previous concept of substantial equivalence, which was developed by industry and the OECD in 1993.[16][20] Substantial equivalence was subject to critique from a variety of experts and stakeholders, including Esther Kok and Harry Kuiper who in 2003, while working for the ILSI Task Force, argued that substantial equivalence should be renamed comparative assessment with no change to its core content, and could be used in risk assessment for genetically engineered organisms:

- Although the Principle of Substantial Equivalence has received comments from all types of stakeholders (producers, regulators, consumers, evaluators, etc.), the basic idea behind the principle remains untouched. When evaluating a new or GM crop variety, comparison with available data on the nearest comparator, as well as with similar varieties on the market, should form the initial part of the assessment procedure.[21]

The new concept of comparative assessment was first discussed in a joint working group of the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) and World Health Organisation (WHO) (FAO/ WHO, 2000) chaired by Harry Kuiper[22] As the Testbiotech report authors note, 'Between 2001 and 2003 the concept was shaped by Harry Kuiper and his colleagues to its present day form.'[16]

Making references to the publication by Kuiper et al (2001) and the FAO/WHO workshop, a 2004 report from ILSI on its task force refers to the concept of comparative assessmentas follows:

- This comparative assessment process (also referred to as the concept of substantial equivalence) is a method of identifying similarities and differences between the newly developed food or feed crop and a conventional counterpart that has a history of safe use.[15]

In 2003 Harry Kuiper became head of the newly established EFSA GMO Panel, the group of experts responsible for the risk assessment of genetically engineered plants. Suzy Renckens, who was head of EFSA's GMO Unit at this time, became the centre of controversy when she joined agri-biotech corporation Syngenta immediately upon leaving EFSA in 2008.[23] [24]

The EFSA Guidance Document[25] for the risk assessment of food and feed derived from genetically engineered plants was produced by the team around Kuiper and Renckens, with comparative assessment constituting the document's 'most crucial element'. Co-authors include the German experts Detlev Bartsch, Hans-Joerg Buhk and Joachim Schiemann.[23] Their connections with the GM industry is described by Lorch and Then (2008).[26] As the Testbiotech report notes:

- Kuiper and his colleagues were active in several organizations (such as ILSI, EFSA, FAO/WHO and ENTRANSFOOD) and prepared several papers published in scientific magazines. This could give the impression that the concept of Comparative Assessment relies on a broad consensus of all kind of experts. On taking a closer look, however, it seems that to a large extent the concept was created just by the network around Harry Kuiper and his colleagues during the time he was active for the ILSI Task Force (see Table 1).[23]

As the Testbiotech report explains, the ILSI itself claims the EFSA guidelines as a success of its Task Force. Kevin Glenn - of Monsanto and the chair of the ILSI Task Force - suggested at a workshop in 2006 that the ILSI (2004) report had had an impact.[1] The negotiations on the international standards contained in the Codex Alimentarius were also influenced by the ILSI report, as set out by ILSI in 2008:

- In 2002, a task force of international scientific experts, convened by the ILSI Intl. Food Biotechnology Committee (IFBiC), addressed the topic of the safety and nutritional assessments of foods and feeds that are nutritionally improved through modern biotechnology. In 2004, the task force’s work culminated in the publication of a report that included a series of recommendations for the nutritional and safety assessments of such foods and feeds. This document has gained global recognition from organizations such as the European Food Safety Agency and has been cited by Japan and Australia in 2005 in their comments to Codex Alimentarius. The substantial equivalence paradigm, called the comparative safety assessment process in the 2004 ILSI publication, is a basic principle in the document.[27]

Table 1: Development of the concept of comparative assessment[23]

| Year | Events |

|---|---|

| 1993 | OECD publishes its concept of Substantial Equivalence |

| 1999 | Harry Kuiper writes his first report for ILSI |

| 2000 | Joint workshop of FAO & WHO chaired by Harry Kuiper discusses Comparative Assessment |

| Around 2001 | Harry Kuiper, Gijs Kleter and Ester Kok become authors for the ILSI Task Force |

| 2001-2003 | Harry Kuiper, Gijs Kleter and Ester Kok publish several papers on the risk assessment of genetically engineered plants and the concept of Comparative Assessment is given its current shape. |

| 2003 | Harry Kuiper, Gijs Kleter and Suzy Renckens become staff members of the EFSA GMO Panel |

| 2004 | The ILSI Task Force publishes its report particularly emphasising the concept of the Comparative Assessment |

| 2004 | EFSA publishes its Guidance Document on the risk assessment of food and feed derived from genetically engineered plants. Comparative Assessment is hereby the most important starting point |

Further cooperation between ILSI and EFSA

As Testbiotech notes[28], the ILSI report (2004) and the EFSA's Guidance Document (2004) are not the only examples of collaboration between Harry Kuiper and Gijs Kleter and ILSI. Kuiper and Kleter were both members of the EFSA GMO Panel (Kuiper stood down in 2012, while Kleter remains). Kuiper ́s declaration of interests on the EFSA website reveals that at that stage he was also working with ILSI.[28] Kleter was a member of the ILSI Task Force until 2007 (see Figure 4).

The ILSI has had further impact on the EFSA, as the Testbiotech report sets out:

- [S]triking indications for ILSI impact are evident in the EFSA position on animal feeding studies (EFSA, 2007). EFSA does not normally require feeding studies with genetically engineered plants to test them for potential health impacts (for overview see Then & Potthoff, 2009). The document published by EFSA to explain why feeding trials are not necessary, was at least partially plagiarized from an ILSI paper.[28]

An overview of passages containing 'more or less the same wording' as in the EFSA (2007) and ILSI (2004) reports is provided in Table 2 below. As the Testbiotech report notes, 'It is clearly the case that EFSA copied several passages from the ILSI report.'[28]

Table 2: Overview on paragraphs with similar wording that can be found both in EFSA (2007) and ILSI (2004) reports[29]

| ILSI (2004) | EFSA (2007) |

|---|---|

| In the case of GM crops with improved nutritional characteristics, livestock feeding studies with target species should be conducted on a case-by-case basis to establish the nutritional benefits that might be expected. | Livestock feeding studies with target animal species should be conducted on a case-by-case basis to establish the nutritional benefits that might be expected from GM plants with claimed nutritional/health benefits. |

| In addition, livestock feeding studies with target species are sometimes conducted to establish the effect of the new feed resource on animal performance with endpoint measurements such as feed intake, level of animal performance, feed conversion efficiency, animal health and welfare, efficacy, and acceptability of the new feed ingredient. | Livestock feeding studies with target species are sometimes conducted to establish the effect of a new feed material on animal performance with endpoint measurements such as feed intake, animal performance, feed conversion efficiency, animal health and welfare, efficacy, and acceptability of the new feed material. |

| In the case where nutritional components are to be deposited in the consumed tissue of the animal, specific tests for content should be conducted. | In cases where GM plants have been fed to livestock with the intention of modifying the nutritional components to be deposited in the consumed tissue of the animal, specific tests for content should be conducted. |

| The extent and type of livestock feeding studies conducted will depend on the type of feed resource developed, and their need should be determined on a case-by-case basis. | The extent and type of livestock feeding studies conducted will depend on the type of feed material developed, and their need should be determined on a case-by-case basis. |

| Sidhu and others (2000) and Ridley and others (2002) provide an excellent example of the compositional analyses conducted when comparing the grain and forage component of maize modified for an agronomic trait with its near isogenic counterpart and a number of commercially grown varieties. | The work conducted by Ridley et al. (2002) provides an excellent example of the extensive compositional analyses conducted when comparing the grain and forage component of HT maize (NK603) with its near isogenic counterpart and a number of commercially grown varieties. |

| Table 2-1: Examples of crops genetically modified with nutritionally improved traits intended to provide health benefits to consumers and domestic animals. | Table 1 Examples of GM plants with improved characteristics intended to provide nutritional or other health benefits to consumers and/or domestic animals |

| Once compositional equivalence, which is a cornerstone in nutritional assessment, has been demonstrated, work then focuses, if necessary, on livestock feeding studies to confirm nutritional equivalence (see Appendix 5-1) and on assessing the safety of any newly expressed components (proteins or nutrients). | Once compositional equivalence of the GM plant has been demonstrated, work may then be focused, where necessary, on livestock feeding studies to confirm nutritional equivalence, and to obtain further information on the safety. |

| Several crops with genetic modifications aimed at improving nutritional characteristics have been produced and are currently in trials (see Chapter 2). | A number of plants with genetic modifications aimed at improving nutritional characteristics have been developed (Table 1) and are currently in trials. |

| The exact experimental and statistical design will depend on a number of factors and will include animal species used in the study, the trait(s) being assessed, and the size of expected effect, which will in turn affect, for example, the number of animals per treatment group. | The exact experimental and statistical design of animal experiments to test the safety and nutritional value of GM plants with enhanced nutritional characteristics will depend on a number of factors and will include animal species, plant trait(s) and the size of the expected effect. |

Furthermore, the outcome of comparative assessment is reached using data from a databank created by the ILSI.[30] This databank is used to compare data from genetically engineered plants with conventional plant data. As Testbiotech notes:

- The broader the range of ILSI data that is used in the comparison, the less a change in the components of genetically engineered plants will be judged as biologically relevant.

- This procedure involving the comparison of data from industry (from genetically engineered plants) with the data from the ILSI databank does not appear to provide adequate protection from manipulation. It cannot be ruled out that data from industry is adapted to correspond with data from the ILSI databank.[6].

The ILSI databank was used to complete a risk assessment of SmartStax, a genetically engineered maize with eight additional gene constructs.[31] Comparative assessment was carried out with data from the ILSI databank but revealed nothing noteworthy and therefore EFSA concluded that it was not necessary to perform further risk assessment.

- [T]he maize MON 89034 x 1507 x MON 88017 x 59122, as described in this application, is as safe as its conventional counterpart and commercial maize varieties with respect to potential effects on human and animal health and the environment.

- ...[It] is unlikely to have adverse effects on human and animal health and the environment, in the context of its intended uses.[31]

The EFSA published new guidelines on environmental risk assessment for genetically engineered plants in 2010[32] which are similarly based on comparative assessment.[6]

Resources

- EFSA (2004) Guidance document of the Scientific Panel on Genetically Modified Organisms for the risk assessment of genetically modified plants and derived food and feed, the EFSA Journal (2004) 99, 1–94

- EFSA (2007) Assessment of Genetically Modified Plants and Derived Food and Feed: The Role of Animal Feeding Trials – Report of the EFSA GMO Panel working group on animal feeding trials, Adopted by the Scientific panel on Genetically Modified Organisms on 12 September 2007. Food and Chemical Toxicology, Volume 46, Supplement 1, March 2008

- EFSA (2010) Panel on Genetically Modified Organisms (GMO); Guidance on the environmental risk assessment of genetically modified plants, EFSA Journal 2010;8(11):1879

- EU (2006) EU Press release IP/06/498, Brussels, 12 April 2006: Commission proposes practical improvements to the way the European GMO legislative framework is implemented

- FAO/WHO (2000) Safety aspects of genetically modified foods of plant origin, Report of a Joint FAO/WHO Expert Consultation on Foods Derived from Biotechnology, World Health Organization, Headquarters, Geneva, Switzerland, 29 May – 2 June 2000

- FAO/WHO (2005) Joint FAO/WHO Food Standards Program Codex ad Hoc intergovernmental task force on foods derived from biotechnology, Fifth Session, Chiba, Japan, 19–23 September 2005, CX/FBT 05/5/4

- ILSI (1999) Detection methods for novel foods derived from genetically modified organisms, ILSI Europe Report Services, Summary of a workshop held in June 1998, Organised by the ILSI Europe Novel Food Task Force in collaboration with the ILSI International Food Biotechnology Committee.

- ILSI (2004) Nutritional and safety assessments of foods and feeds nutritionally improved through biotechnology. Prepared by a Task Force of the ILSI International Food Biotechnology Committee as published in IFT’s Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 2004 Institute of Food Technologists (www.ift.org)

- ILSI (2008) Assessments of Foods and Feeds Nutritionally Improved through Biotechnology: Case Studies Prepared by a Task Force of the ILSI International Food Biotechnology Committee, Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, Vol. 7, 53–113

- Kok, E.J. and H. A. Kuiper (2003) Comparative safety assessment for biotech crops. Trends in Biotechnology 21: 439–444.

- Kuiper H. A., G. A. Kleter, H. P. J. M. Noteborn, and E. J. Kok (2001) Assessment of the food safety issues related to genetically modified foods. Plant J 27:503–28.

- Kuiper H.,A. and G. A. Kleter (2003) The scientific basis for risk assessment and regulation of genetically modified foods, Trends in Food Science & Technology 14 (2003) 277–293

- Lorch A. and C. Then (2008) Kontrolle oder Kollaboration? Bericht für die Grünen im Deutschen Bundestag, in German only

- OECD (1993) channelId=34537&homeChannelId=33703&fileTitle=Safety+Considerations+for+Biotechnology+ Scale-up+of+Crop+Plants Safety Considerations for Biotechnology: Scale-up of Crop Plants

- Then, C. and A. Bauer-Panskus (2010) Testbiotech report, European Food Safety Authority: A playing field for the biotech industry, 2010, accessed 9 January 2013.

- Then, C. and C. Potthoff (2009) Risk Reloaded – Risk analysis of genetically engineered plants within the European Union, Testbiotech report, www.testbiotech.org

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Testbiotech (2010), "European Food Safety Authority: A playing field for the biotech industry," Testbiotech report, p2, accessed 9 January 2013. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "pagetwo" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Directive 2001/18 (2003), Regulation 1829/2003 on genetically modified food and feed, accessed 12 January 2013

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Testbiotech (2010), "European Food Safety Authority: A playing field for the biotech industry," Testbiotech report, p3, accessed 9 January 2013.

- ↑ EU Commission (2006), Commission proposes practical improvements to the way the European GMO legislative framework is implemented, accessed 12 January 2013

- ↑ Testbiotech (2010), EU Commission to dump risk assessment of genetically engineered plants?, accessed 20 January 2013

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Testbiotech (2010), "European Food Safety Authority: A playing field for the biotech industry," Testbiotech report, p10, accessed 9 January 2013.

- ↑ ILSI (2008), Nutritional and Safety Assessments of Foods and Feeds Nutritionally Improved through Biotechnology: Case Studies, Prepared by a Task Force of the ILSI International Food Biotechnology Committee, Volume 7, Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, p53, accessed 13 January 2013

- ↑ World Health Organisation (2001), The Tobacco Industry and Scientific Groups ILSI: A Case Study, accessed 12 January 2013

- ↑ Sean Poulter (2012), EU watchdog forced out over links to 'Frankenstein food' firms, Daily Mail, 5 May 2012, accessed 12 January 2013

- ↑ Nils Klawitter (2010), Efsa-Wissenschaftler spülen Bisphenol A weich, Spiegel Online, 18 November 2010, accessed 12 January 2013

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Testbiotech (2010), "European Food Safety Authority: A playing field for the biotech industry," Testbiotech report, p4, accessed 9 January 2013.

- ↑ ILSI (2013), Task Force on Nutritional and Safety Assessments of Foods and Feeds Nutritionally Improved through Biotechnology, accessed 13 January 2013

- ↑ Monsanto, For the Record–Science: Food Safety, p2, accessed 13 January 2013

- ↑ ILSI (1999), Detection methods for novel foods derived from genetically modified organisms, ILSI Europe Report Services, Summary of a workshop held in June 1998, accessed 13 January 2013

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 ILSI (2004), Nutritional and safety assessments of foods and feeds nutritionally improved through biotechnology, Prepared by a Task Force of the ILSI International Food Biotechnology Committee, Institute of Food Technologists, accessed 13 January 2013

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 Testbiotech (2010), "European Food Safety Authority: A playing field for the biotech industry," Testbiotech report, p5, accessed 15 January 2013

- ↑ ILSI (2008), Assessments of Foods and Feeds Nutritionally Improved through Biotechnology: Case Studies Prepared by a Task Force of the ILSI International Food Biotechnology Committee, Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, Vol. 7, 53-113, accessed 13 January 2013

- ↑ EFSA (2004), Guidance document of the Scientific Panel on Genetically Modified Organisms for the risk assessment of genetically modified plants and derived food and feed, the EFSA Journal, 99, 1–94, p12, accessed 20 January 2013

- ↑ EFSA (2004), Guidance document of the Scientific Panel on Genetically Modified Organisms for the risk assessment of genetically modified plants and derived food and feed, the EFSA Journal, 99, 1–94, p13, accessed 20 January 2013

- ↑ OECD, (1993), channelId=34537&homeChannelId=33703&fileTitle=Safety+Considerations+for+Biotechnology+ Scale-up+of+Crop+Plants Safety Considerations for Biotechnology: Scale-up of Crop Plants, accessed 20 January 2013

- ↑ Kok, E. & Kuiper, H. (2003),, Comparative safety assessment for biotech crops, Trends in Biotechnology, 21, 439–444

- ↑ FAO/WHO (2000), [www.who.int/foodsafety/publications/biotech/ec_june2000/en/ Safety aspects of genetically modified foods of plant origin], Report of a Joint FAO/WHO Expert Consultation on Foods Derived from Biotechnology, World Health Organization, Headquarters, Geneva, Switzerland, 29 May – 2 June 2000, accessed 20 January 2013

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 Testbiotech (2010), "European Food Safety Authority: A playing field for the biotech industry," Testbiotech report, p6, accessed 20 January 2013.

- ↑ Testbiotech (2010), Head of department moves from European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) to biotech company within two months, accessed 20 January 2013

- ↑ EFSA (2004), Guidance document of the Scientific Panel on Genetically Modified Organisms for the risk assessment of genetically modified plants and derived food and feed, the EFSA Journal, 99, 1–94, accessed 20 January 2013

- ↑ Lorch & Then (2008), Control or Collaboration? Agro-biotechnology and the role of the authorities, currently available in German only, accessed 20 January 2013

- ↑ ILSI (2008), Assessments of Foods and Feeds Nutritionally Improved through Biotechnology: Case Studies Prepared by a Task Force of the ILSI International Food Biotechnology Committee, Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, Vol. 7, 53–113, p54, accessed 20 January 2013

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 Testbiotech (2010), "European Food Safety Authority: A playing field for the biotech industry," Testbiotech report, p8, accessed 20 January 2013

- ↑ Testbiotech (2010), "European Food Safety Authority: A playing field for the biotech industry," Testbiotech report, p9, accessed 20 January 2013.

- ↑ ILSI, (2006), International Life Sciences Institute Crop Composition Database Version 3.0. Available from: http://www.cropcomposition.org

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 EFSA (2010), Scientific Opinion on application (EFSA-GMO-CZ-2008-62) for the placing on the market of insect resistant and herbicide tolerant genetically modified maize MON 89034 x 1507 x MON 88017 x 59122 and all sub-combinations of the individual events as present in its segregating progeny, for food and feed uses, import and processing under Regulation (EC) No 1829/2003 from Dow AgroSciences and Monsanto , accessed 20 January 2013

- ↑ EFSA (2010), Panel on Genetically Modified Organisms (GMO); Guidance on the environmental risk assessment of genetically modified plants, EFSA Journal 2010;8(11):1879, accessed 20 January 2013